July 25, 2023

Some of our most important everyday items, like computers, medical equipment, stereos, generators, and more, work because of magnets. We know what happens when computers become more powerful, but what might be possible if magnets became more versatile? What if one could change a physical property that defined their usability? What innovation might that catalyze?

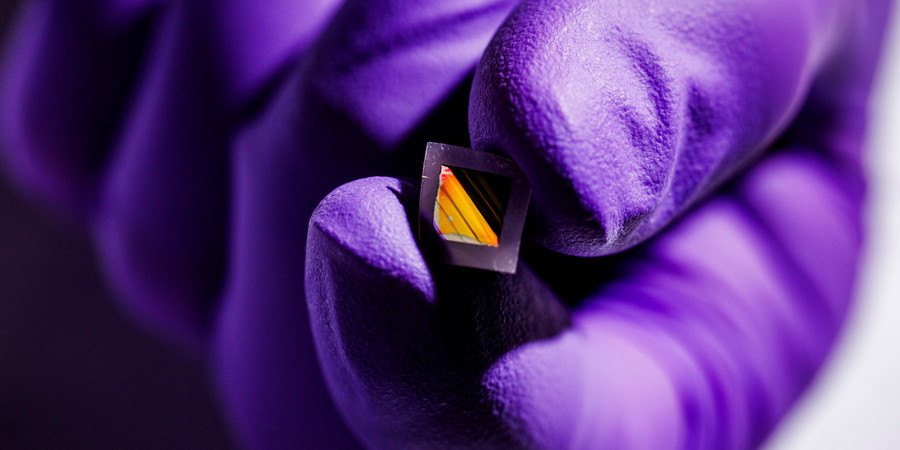

It’s a question that MIT Plasma Science and Fusion Center (PSFC) research scientists Hang Chi, Yunbo Ou, Jagadeesh Moodera, and their co-authors explore in a new open-access Nature Communications paper, “Strain-tunable Berry curvature in quasi-two-dimensional chromium telluride.”

Understanding the magnitude of the authors’ discovery requires a brief trip back in time: In 1879, a 23-year-old graduate student named Edwin Hall discovered that when he put a magnet at right angles to a strip of metal that had a current running through it, one side of the strip would have a greater charge than the other. The magnetic field was deflecting the current’s electrons toward the edge of the metal, a phenomenon that would be named the Hall effect in his honor.

In Hall’s time, the classical system of physics was the only kind, and forces like gravity and magnetism acted on matter in predictable and immutable ways: Just like dropping an apple would result in it falling, making a “T” with a strip of electrified metal and magnet resulted in the Hall effect, full stop. Except it wasn’t, really; now we know quantum mechanics plays a role, too.

Complete article from MIT News.

Explore

MIT Engineers Advance Toward a Fault-tolerant Quantum Computer

Adam Zewe | MIT News

Researchers achieved a type of coupling between artificial atoms and photons that could enable readout and processing of quantum information in a few nanoseconds.

III-Nitride Ferroelectrics for Integrated Low-Power and Extreme-Environment Memory

Monday, May 5, 2025 | 4:00 - 5:00pm ET

Hybrid

Zoom & MIT Campus

New Electronic “skin” could Enable Lightweight Night-vision Glasses

Jennifer Chu | MIT News

MIT engineers developed ultrathin electronic films that sense heat and other signals, and could reduce the bulk of conventional goggles and scopes.